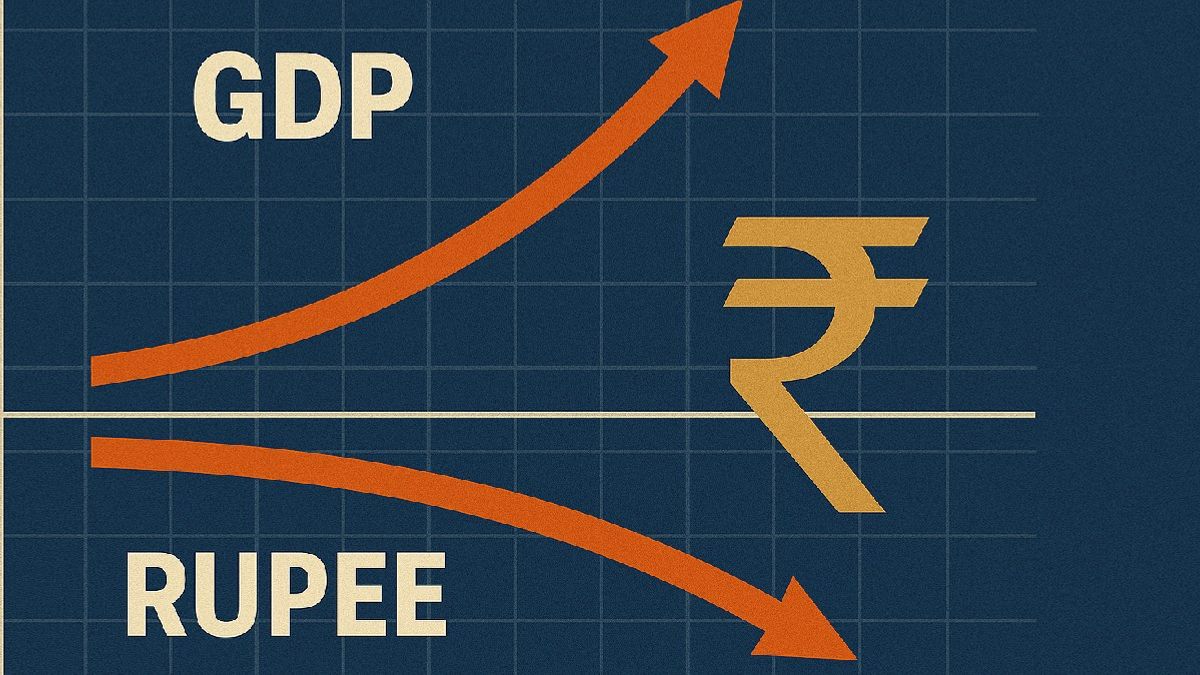

High Economic Growth Is Not Enough to Stem Falling Rupee

Since independence in 1947, the Indian rupee has shown a clear long-term trend of gradual depreciation against the U.S. dollar, moving from Rs 3.30 per USD to Rs 83.4 in 2024 and approximately Rs 90 per USD by the end of 2025. The pace of depreciation has varied across decades, reflecting both domestic policies and global economic conditions. In the early years (1947-1966), the rupee declined at about 4.4% per year under a fixed exchange system linked to the British pound. Between 1966 and 1976, depreciation slowed to 1.8% annually following the 1966 devaluation and tighter controls. The 1976-1986 period saw a slightly faster decline of 3.5% per year due to oil shocks and fiscal pressures, while 1986-1996 witnessed the sharpest depreciation at 10.9% annually, driven by the balance-of-payments crisis and the shift to a market-determined exchange rate. Post-liberalization, from 1996 onwards, the rupee's decline became more moderate and stable: 3.0% per year during 1996-2004, 2.9% per year in 2004-2014, and 3.3% per year from 2014-2024. Overall, while depreciation is structural, policy reforms and economic stabilization after the 1990s have made the trend smoother and more predictable. Though, rupee has depreciated more sharply in the last one year by 4.7 percent, this looks like a short term phenomenon. It is a common belief that a strong economy would mean that its currency would also be stronger. But in present times, this belief is being belied. We see that in the last nearly one decade, India's economy has been growing at a rate, faster than other large economies; and has the distinction of being the fastest growing economy of the world for the last nearly five years. Size of Indian economy (GDP) has grown from 2.07 trillion US dollars in 2014 to 4.18 trillion US dollars in 2025. In the last more than 75 years of Independence, India has been growing at a much faster rate as compared to the growth rate before 1947; and more recently also compared to the growth rate of its peers. It's interesting to note that in the last two years, the movement in rupee dollar exchange rate has not been uniform. After a relatively stable exchange rate between April 2023 and mid-2025, the exchange rate has gone volatile and rupee depreciated by more than 6 percent in only 6 months from approximately Rs. 85 per dollar to more than Rs. 90 per dollar. Interestingly, in the preceding quarter, India's GDP growth has reached 8.2 percent, which is considered to be fairly good, amidst geopolitical tensions due to conflicts and wars; and disturbed global economy, due to unprecedented tariff war, initiated by President Trump of US. Rapid economic growth should normally strengthen a country's currency. However, India often experiences a paradox where GDP growth remains high and its currency depreciates significantly. There is a need to understand this paradox, as exchange rate movements are not determined by GDP growth, but by multiplicity of factors, which have bearing on demand and supply of foreign exchange. In other words, there are number of structural and macroeconomic factors, which have bearing on the exchange rates.

Firstly, exchange rates are driven more by capital flows than by GDP growth alone. Even with strong growth, if foreign investors pull out capital due to global uncertainty, rising interest rates in their home country/countries, or risk aversion, the rupee can weaken. This is exactly, what has happened in India; in 2025 itself, Foreign Portfolio Investors (FPIs) have withdrawn 18.4 billion US dollars from Indian stock markets till December 15, 2025, not due to any weakness in Indian economy, but due to their own reasons.

Secondly, instead of strengthening, higher GDP growth may even cause rupee depreciation. High growth in India is often import-intensive, especially for crude oil, electronics, and capital goods. Rising imports widen the current account deficit, increasing demand for dollars and putting downward pressure on the rupee. We see that manufacturing of electronics, automobiles, machinery and many more sectors necessitate imports of components and raw materials, meaning thereby, more demand for foreign exchange, exerting pressure on rupee. Moreover, increased manufacturing serves domestic more than exports, therefore, less earning than spending of foreign exchange. In this regard we find that deficit in India's merchandise increased from 240 billion US dollars in 2023-24 to 282.2 billion US dollars in 2024-25.

Thirdly, dollar's dominance and global monetary tightening have also been making rupee weaken, which is beyond the scope of Indian economy. Periods of tightening by the US Federal Reserve-strengthen the dollar against most currencies. In such phases, rupee depreciation reflects global dollar strength, not necessarily domestic weakness.

Fourthly, inflation obviously cause decline in the value of currency. In India's case, in the past, high inflation had also been one of major causes for rupee to depreciate. In the last one decade, especially in the last decade, prices have relatively stabilised, and so was the exchange rate. Inflation differentials in the past had been one of the determinants of the differentials in the value of the currencies. If India's inflation remains higher than that of advanced economies, the rupee tends to depreciate over time to maintain purchasing power parity, even during high growth.

Fifthly, much of India's growth is driven by domestic consumption and public investment rather than exports. if the growth is led by domestic demand, without a commensurate rise in export competitiveness, it does not automatically translate into currency appreciation.

Sixthly, sometimes government may on its own try to depreciate rupee, to maintain the competitiveness of our exports. Therefore, sometimes, depreciation of rupee is also a policy choice, not actually a failure. Economists and policy makers generally believe that moderately depreciating rupee can support exports, discourage non-essential imports, and protect domestic industry. In essence, high growth reflects real economic expansion, while the rupee reflects relative prices, capital movements, and global financial conditions. The coexistence of the two is not a paradox but a feature of a globally integrated yet structurally import-dependent economy, like ours.