Matallurgy in Ancient India (Part-3)

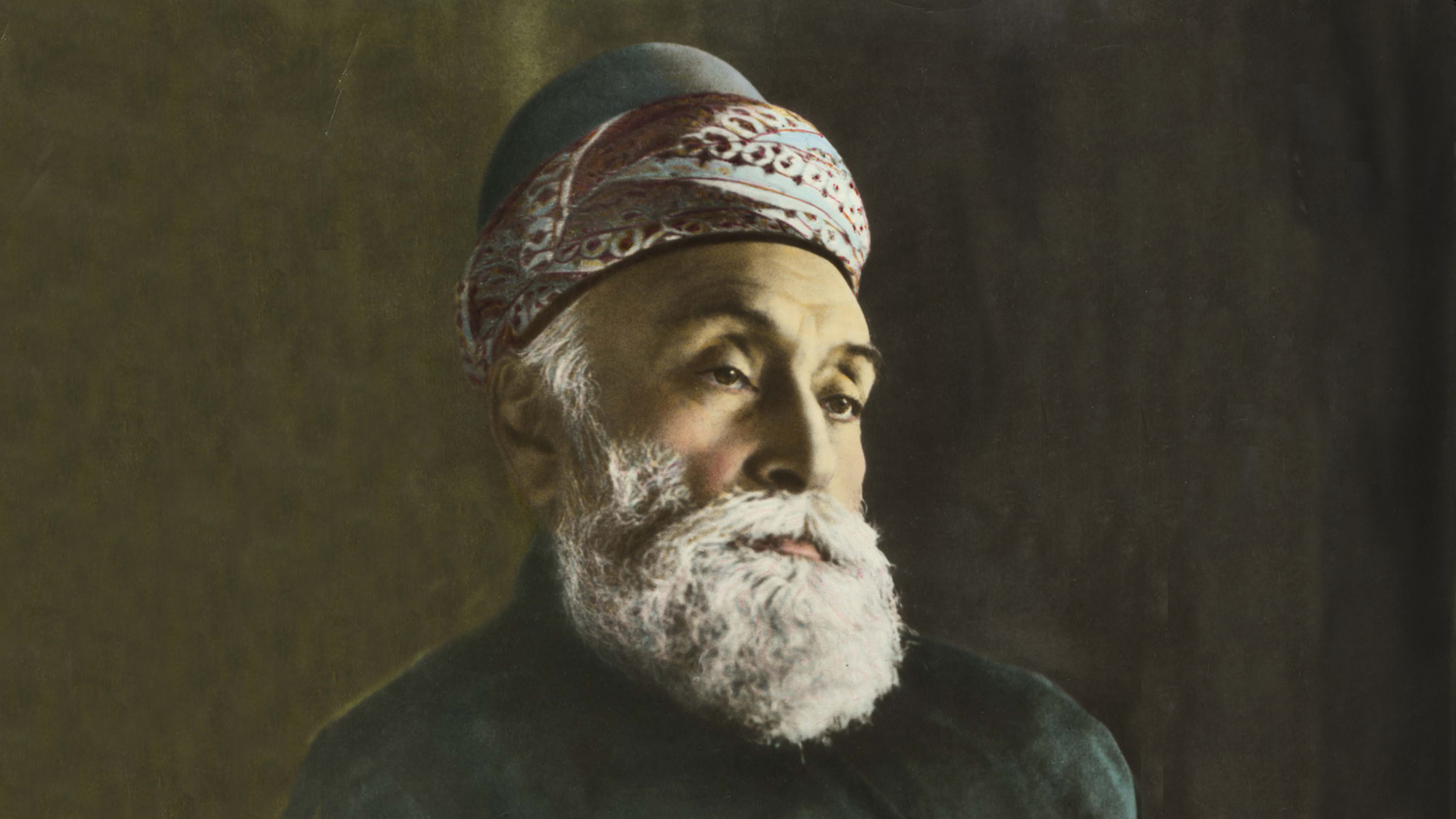

After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, many Indian wootz steel swords were ordered to be destroyed by the East India Company. The metalworking industry in India went into decline during the period of British Crown control due to various colonial policies, but steel production was revived in India by Jamsetji Tata. — Prof. Nandini Sinha Kapur

Henry Yule quoted the 12th-century Arab Edrizi who wrote: “The South Indians excel in the manufacture of iron, and in the preparations of those ingredients along with which it is fused to obtain that kind of soft iron which is usually styled Indian steel. They also have workshops wherein are forged the most famous sabres in the world. It is not possible to find anything to surpass the edge that you get from Indian steel (al-hadid al-Hindi).

As early as the 17th century, Europeans knew of India’s ability to make crucible steel from reports brought back by travelers who had observed the process at several places in southern India. Several attempts were made to import the process, but failed because the exact technique remained a mystery. Studies of wootz were made in an attempt to understand its secrets, including a major effort by the famous scientist, Michael Faraday, son of a blacksmith. Working with a local cutlery manufacturer he wrongly concluded that it was the addition of aluminium oxide and silica from the glass that gave wootz its unique properties.

After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, many Indian wootz steel swords were ordered to be destroyed by the East India Company. The metalworking industry in India went into decline during the period of British Crown control due to various colonial policies, but steel production was revived in India by Jamsetji Tata.

Zinc

Zinc was extracted in India as early as in the 4th to 3rd century BCE. Zinc production may have begun in India, and ancient northwestern India is the earliest known civilization that produced zinc on an industrial scale. The distillation technique was developed around 1200 CE at Zawar in Rajasthan.

In the 17th century, China exported Zinc to Europe under the name of totamu or tutenag. The term tutenag may derive from the South Indian term Tutthanagaa (zinc). In 1597, Libavius, a metallurgist in England received some quantity of Zinc metal and named it as Indian/Malabar lead. In 1738, William Champion is credited with patenting in Britain a process to extract zinc from calamine in a smelter, a technology that bore a strong resemblance to and was probably inspired by the process used in the Zawar zinc mines in Rajasthan. His first patent was rejected by the patent court on grounds of plagiarising the technology common in India. However, he was granted the patent on his second submission of patent approval. Postlewayt’s Universal Dictionary of 1751 still wasn’t aware of how Zinc was produced.

The Arthashastra describes the production of zinc. The Rasaratnakara by Nagarjuna describes the production of brass and zinc. There are references of medicinal uses of zinc in the Charaka Samhita (300 BCE). The Rasaratna Samuchaya (800 CE) explains the existence of two types of ores for zinc metal, one of which is ideal for metal extraction while the other is used for medicinal purpose It also describes two methods of zinc distillation.

Early history (—200 BCE)

Recent excavations in Middle Ganges Valley conducted by archaeologist Rakesh Tewari show iron working in India may have begun as early as 1800 BCE. Archaeological sites in India, such as Malhar, Dadupur, Raja Nala Ka Tila and Lahuradewa in the state of Uttar Pradesh show iron implements in the period between 1800 BCE-1200 BCE. Sahi (1979: 366) concluded that by the early 13th century BCE, iron smelting was definitely practiced on a bigger scale in India, suggesting that the date the technology’s early period may well be placed as early as the 16th century BCE.

Some of the early iron objects found in India are dated to 1400 BCE by employing the method of radio carbon dating. Spikes, knives, daggers, arrow-heads, bowls, spoons, saucepans, axes, chisels, tongs, door fittings etc. ranging from 600 BCE—200 BCE have been discovered from several archaeological sites. In Southern India (present day Mysore) iron appeared as early as the 12th or 11th century BCE. These developments were too early for any significant close contact with the northwest of the country.

The earliest available Bronze age swords of copper discovered from the Harappan sites in Pakistan date back to 2300 BCE. Swords have been recovered in archaeological findings throughout the Ganges-Jamuna Doab region of India, consisting of bronze but more commonly copper. Diverse specimens have been discovered in Fatehgarh, where there are several varieties of hilt. These swords have been variously dated to periods between 1700 and 1400 BCE, but were probably used more extensively during the opening centuries of the 1st millennium BCE.

The beginning of the 1st millennium BCE saw extensive developments in iron metallurgy in India. Technological advancement and mastery of iron metallurgy was achieved during this period of peaceful settlements. The years between 322 and 185 BCE saw several advancements being made to the technology involved in metallurgy during the politically stable Maurya period (322—185 BCE). Greek historian Herodotus (431—425 BCE) wrote the first western account of the use of iron in India.

Perhaps as early as 300 BCE—although certainly by 200 CE—high quality steel was being produced in southern India by what Europeans would later call the crucible technique. In this system, high-purity wrought iron, charcoal, and glass were mixed in a crucible and heated until the iron melted and absorbed the carbon. The first crucible steel was the wootz steel that originated in India before the beginning of the common era. Wootz steel was widely exported and traded throughout ancient Europe, China, the Arab world, and became particularly famous in the Middle East, where it became known as Damascus steel. Archaeological evidence suggests that this manufacturing process was already in existence in South India well before the common era.

Zinc mines of Zawar, near Udaipur, Rajasthan, were active during 400 BCE. There are references of medicinal uses of zinc in the Charaka Samhita (300 BCE). The Periplus Maris Erythraei mentions weapons of Indian iron and steel being exported from India to Greece.

Early Common Era—Early Modern Era

The world’s first iron pillar was the Iron pillar of Delhi—erected at the times of Chandragupta II Vikramaditya (375–413), often considered as one of the finest pieces of ancient metallurgy. The swords manufactured in Indian workshops find written mention in the works of Muhammad al-Idrisi (flourished 1154). Indian Blades made of Damascus steel found their way into Persia. European scholars—during the 14th century—studied Indian casting and metallurgy technology.