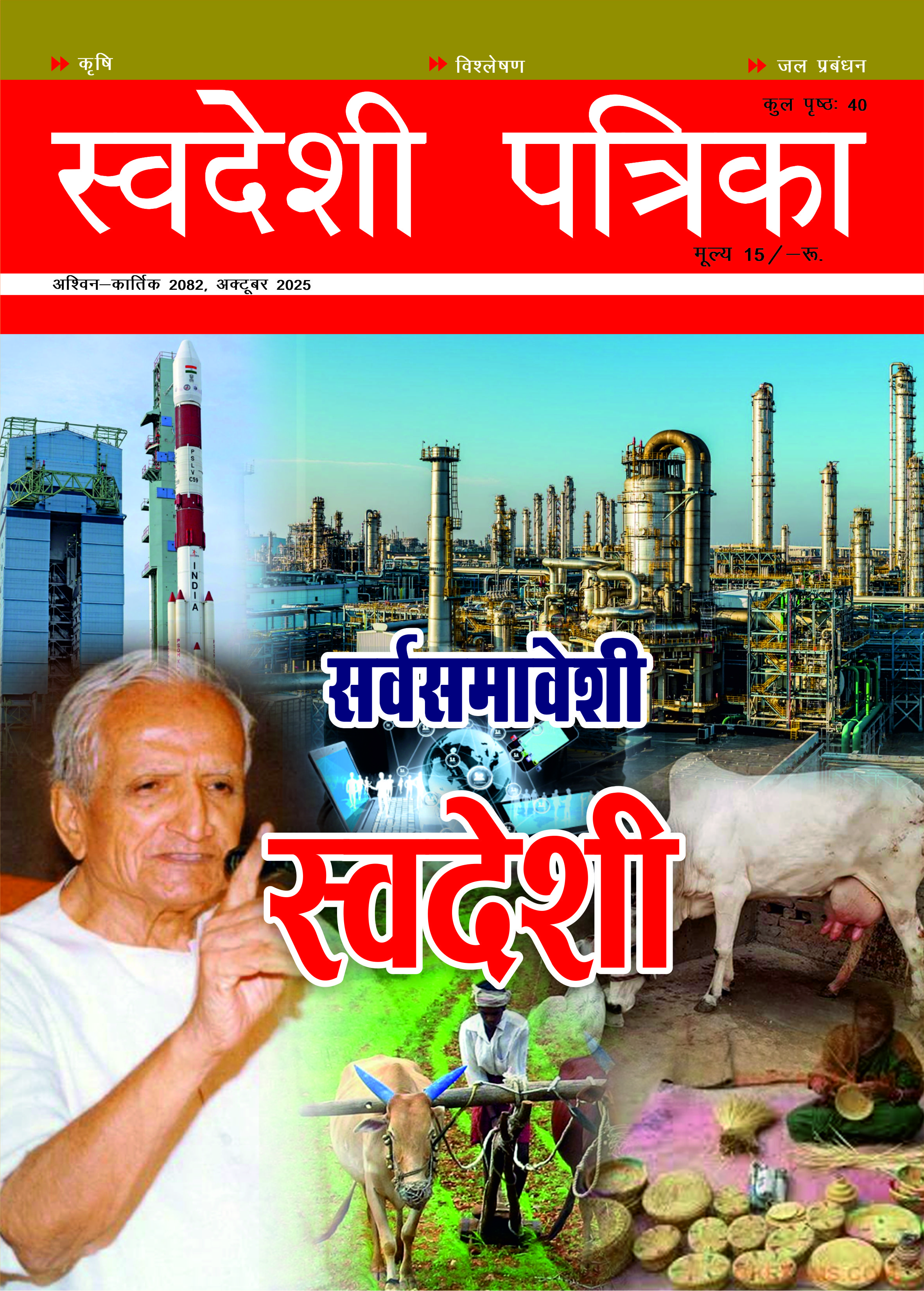

Sangh and Swadeshi: Epitome of selfhood

In the centenary year of the RSS, it’s time to introspect how Panch Parivartan has been giving a boost to Swadeshi. Swadeshi Jagaran Manch is backing Modi Govt’s Atmanirbhar Bharat as it seeks to reduce dependence of foreign capital and tech. The call for boycotting foreign goods was part of the Swadeshi thought process in the past also. — Dr. Ashwani Mahajan

Swadeshi became an instrument of political movement from August 1905, when formal proclamation of the Swadeshi Movement was made. The call for boycotting foreign goods became part of the Swadeshi thought process. This was a practical manifestation of the idea of Swadeshi but the original idea was far beyond boycott of foreign goods. Mahatma Gandhi believed in non-violent industrial development of Bharat. However, after Independence, the Swadeshi movement soon embraced socialism under Jawaharlal Nehru; and got into a phase where terms like ‘selfreliance’ emerged to discredit the private sector and move ahead with the celebration of state-led development, with nationalisation of private enterprises. The centrality of the state replaced the Swadeshi spirit of local enterprises and their vibrancy.

Sangh Opposes Nehruvian Model

Later, in early 90s, the widespread balance of payment crisis, which eventually forced opening of the economy in the 1990s, discredited the development model of ‘self-reliance’ and Swadeshi. Interestingly, Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh opposed the Nehruvian model of state sponsored, public sector led self reliance model. Sangh has equally been vocal against the globalisation model, based on excessive reliance on capital and technology of multinational companies. It’s no secret that economic reforms and opening up of the economy for foreign capital, goods and services, led to severe stress for local enterprises. The new initiative of Atmanirbhar Bharat from 2020, has had full support of Swadeshi Jagaran Manch (SJM), so far as it is aimed at reducing dependence on and domination of foreign capital and technology.

It’s important to understand that the efforts towards self-reliance between 1950 and 1990 were marred with a major problem of minimised role of private sector and individual initiative, which was the major cause of losing international competitiveness. However, the policies of liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation, LPG, also couldn’t do much to make the Bharatiya industrial sector develop, due to excessive reliance on foreign capital and premature opening up of the economy. These policies were vehemently opposed by the Swadeshi Movement of the 1990s onward led by SJM.

In the centenary year of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, one of the five key points for social change, called the Panch Parivartan (five transformations), is ‘Swadeshi’, apart from four others, say ‘Samarasta’ or harmony, environment, ‘Kutumb Prabodhan’ that is family values, and ‘Nagrik Kartavya’ or civic duty have been identified for social change.

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh has played a unique role in nurturing and propagating the Swadeshi ideology over the past 100 years. Its understanding of Swadeshi has never been limited to economic self-reliance; rather, for the Sangh, Swadeshi has been viewed as a civilisational ethos rooted in India’s culture, tradition, and values.

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh was founded at a time when the Swadeshi movement had already gained momentum as part of the freedom struggle. However, for the Sangh, Swadeshi meant not only boycotting foreign goods but also reviving indigenous industries, rural crafts, agriculture, and cultural pride.

Dr Hedgewar believed that for national resurgence, along with political independence, strengthening society through self-reliance in economy and ideas is also essential. In other words, the Sangh has, from its inception, advocated for the boycott of foreign goods as well as widespread Swadeshi for the nation’s revival.

When the Swadeshi Jagran Manch was founded under the leadership of Dattopant Thengadi ji, inspired by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, in response to the issues arising from the resurgence of imperialistic powers, three dimensions were added to the Manch’s work. The first dimension was public awareness, which focused on issues of creating awareness about indigenous goods, local products, and foreign threats.

The second dimension of Swadeshi was agitation. The Swadeshi Jagran Manch organised several movements to maintain Bharat’s economic independence and sovereignty. Initially, the Swadeshi Jagran Manch launched a nationwide movement against the Dunkel Draft to protect the country’s interests in the context of agreements under the GATT. This was followed by a ‘Matsya Yatra’ to protest against deep-sea fishing by trawlers owned by foreign companies (and the resulting threat to small fishermen). Following this, a 107-kilometer-long padayatra was organised from Wardha to Alkabir to protest against the mechanised slaughterhouse at Alkabir. During its 34 years of existence, the Swadeshi Jagran Manch has organised numerous campaigns and movements, most of which have been successful.

The third dimension of the Swadeshi Jagran Manch’s work has been constructive work. It is organising Swadeshi fairs to promote small industries, especially cottage industries, and the skills of artisans. and providing small loans to help economically weaker women to start their small businesses.

Even after Independence, the Sangh held a clear position that political independence was meaningless without economic self-reliance, that is, Swadeshi. The Sangh always opposed excessive dependence on Western models of development and emphasised that India should protect its traditional strengths in agriculture, small-scale industries, and a community-based economy; and develop its indigenous technologies. During the era of the Green Revolution and industrialisation, the Sangh believed that excessive dependence on foreign technology and capital could harm Bharat’s self-reliance. This stand of the Sangh was vindicated, when dependence on foreign capital and technology began to hinder Bharat’s development.

With economic liberalisation in 1991, the Swadeshi Jagran Manch and the Swadeshi movement, inspired by the Sangh, launched a nationwide public awareness campaign about the dangers of economic imperialism, through multinational corporations and globalisation.

The Swadeshi Jagran Manch’s goals were:

- Promoting self-reliant economic policies.

- Opposing indiscriminate foreign investment.

- Strengthening small-scale and cottage industries, agriculture, and agriculture, including khadibased industries.

- Protecting farmers, small traders and traditional businesses from global competition.

SJM consistently campaigned against World Trade Organisation (WTO) agreements, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the retail sector and intellectual property regimes that harmed Bharat’s interests. The Sangh articulated Swadeshi not only as an economic idea, but also as a cultural and spiritual one. Deendayal Upadhyaya’s Integral Humanism (1965), a fundamental philosophy espoused by the Sangh, links Swadeshi to holistic human development rooted in Bharatiya ethos. In contrast to consumerist globalisation, Swadeshi is seen as a way to preserve family, community, and environmentally friendly lifestyles.

For a long time, the Sangh has been striving for a self-reliant India, which resonates with Swadeshi principles. Local production and consumption chains (farm-to-market, khadi, and village industries) are at the core of the Sangh’s thinking. Sangh firmly believes that technological innovation should be based on Indian needs rather than imported models. GDP growth is not important in itself; growth must be balanced with sustainable development, ecology, and tradition. This means that GDP growth must be accompanied by environmental balance, while simultaneously preserving traditions and reducing economic disparities. In recent years, union-affiliated organisations have protested the excessive reliance on imports from China, calling for boycott movements and strengthening indigenous alternatives.