For a long time, several experts in the country had opposed MGNREGA from a long-term perspective, arguing that it leads to labour shortages in agriculture and industry. — Dr. Ashwani Mahajan

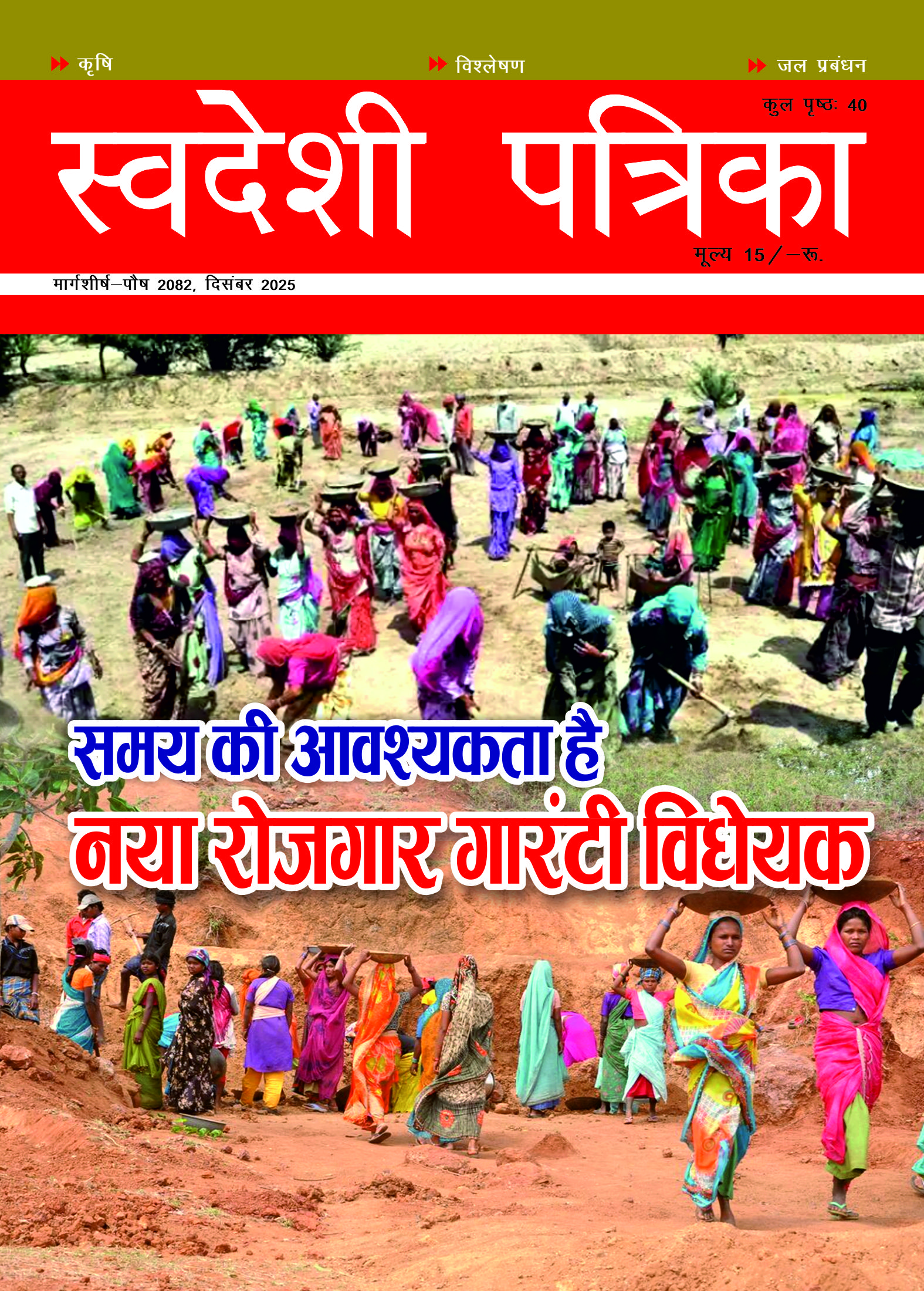

MGNREGA, i.e., the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, is a rights-based rural employment scheme that was enacted in 2005 and implemented from February 2006. It grants every rural household in India a legal right to demand paid work from the state.

Under this Act, any adult member of a rural household aged 18 years or above can apply for work. The government is legally bound to provide up to 100 days of unskilled manual work per household in each financial year, and if work is not provided within 15 days of a written or oral demand, the state must pay an unemployment allowance. For this reason, MGNREGA is not merely a welfare scheme but a legally enforceable right.

There is no employment rights programme of this scale anywhere in the world. Owing to its vast coverage and legal framework, it is unique. This scheme covers crores of rural citizens and grants them employment as a statutory right. During economic shocks such as droughts, agrarian distress, and the COVID-19 pandemic, it served as an economic safety net when millions of migrant workers returned to their villages and depended on this scheme.

Proposing major changes to this scheme, the Viksit Bharat – Rural Employment and Livelihood Guarantee Mission Bill, 2025 (VB-GRAMG) was introduced in Parliament on 16 December, and if passed, will now replace MGNREGA. While the government is presenting the new Bill as a reform aligned with the vision of a Developed India, the opposition is strongly opposing it.

The opposition argues that the government is deliberately indulging in politics by removing Mahatma Gandhi’s name from the law. Further, since the abbreviated name of the Bill would become VBGRAMG, or colloquially “Viksit Bharat G Ram G,” the opposition finds it objectionable. The debate around the Bill has taken the form of a verbal battle; and real provisions in the bill are not being discussed at all. What is needed today is a detailed understanding of the Bill—what its provisions actually are, and what benefits or drawbacks it may bring for the country and rural India.

The thinking behind the Act framed in 2005 was to protect people in rural areas from poverty caused by unemployment by guaranteeing them income, while simultaneously undertaking rural development works such as water conservation projects, irrigation canals, rural roads, flood control structures, and land development activities.

The entire responsibility for financing this scheme lays with the central government, because the underlying idea was that employment is a right, and if it is not available, the government is obligated to provide it. Any person who registered under the scheme had to be provided 100 days of employment, through which they could be engaged in the above-mentioned construction and development works.

It must be understood that this scheme is demand-driven. According to government data, although wage rates under the scheme have been increased over the years to make it more attractive, there has been a sharp decline in the number of days for which people are registering to seek work. This implies that rural people are now finding alternative sources of employment that are more attractive than MGNREGA. The economic condition of rural populations has also improved. Today, the resolve to become Developed India is strengthening day by day. Since 2005, the country has undergone significant changes, and therefore the government believes that fundamental changes in the MGNREGA law are also necessary.

Now States Will Also Fund the Scheme

Although the Bill provides for increasing guaranteed employment from 100 days to 125 days, and up to 150 days in tribal areas, its financing will no longer be the sole responsibility of the central government. Instead, both the central and state governments will share this responsibility. It is noteworthy that in 2005, the states’ share in central revenues was only 32 percent, which was later increased to 42 percent by 14th Finance Commission. States’ share was increased, so that they could bear the burden of welfare schemes. However, since the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act had already been enacted earlier, this burden could not be imposed on the states at that time.

From NREGA to MGNREGA in 2009

Although the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) was passed in 2005 and implemented in 2006 to legally recognise the right to employment, it was renamed the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act by the then UPA government in 2009. Now that a new Avtar of the scheme has been proposed by Parliament in the context of the nation’s resolve to become Viksit Bharat, a change in name was obvious. Coincidentally, the new name resembles that of Lord Ram, who is deeply revered in the country. It is this aspect that the opposition is objecting to.

Availability of Labour for Agriculture

The objective of MGNREGA was to provide income security during periods of unemployment. However, during the sowing and harvesting seasons, workers often remained attracted to MGNREGA, leading to a shortage of labour in farms. This shortage increased wage cost and reduced the competitiveness of agriculture. The new Bill addresses this issue by providing that the employment guarantee programme will be suspended for 60 days required for agricultural activities. Additionally, the nature of works under the programme has also been updated in line with present needs, including water security, rural infrastructure, livelihood-related infrastructure, and mitigation of extreme weather events. These works have also been linked with the PM Gati Shakti National Master Plan.

Curbing Corruption

The biggest flaw of MGNREGA was that despite numerous efforts, corruption could not be fully contained. Corruption at the gram panchayat and block levels led to large-scale misuse of public funds. There were several instances where projects existed only on paper, with no physical existence on the ground. To eliminate corruption, the new Bill provides for the use of modern technology, including biometric authentication for transactions, geospatial technology for planning and monitoring, mobile application–based dashboards for real-time monitoring, and a weekly public disclosure system. Notably, the use of technology in the Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana has already placed significant checks on corruption, and on similar lines, technology can help curb corruption in the employment guarantee programme as well.

For a long time, several experts in the country had opposed MGNREGA from a long-term perspective, arguing that it leads to labour shortages in agriculture and industry. While the new Act has attempted to address the issue of labour shortages in agriculture to some extent, it was also necessary to address the shortage of labour for industry and allied agricultural activities caused by MGNREGA. Had the opposition, instead of raking up unnecessary issues such as naming, engaged in a substantive debate in Parliament to incorporate provisions aligned with the country’s needs, more improvements could have been included in this new Avtar of MGNREGA. Unfortunately, that did not happen.