US Hegemony: Legal and Financial Toolkits

Amidst the global turmoil and the economic uncertainties, Swadeshi is the only panacea for global peace and prosperity. — Dr. Dhanpat Ram Agarwal

The United States today wields immense global influence not just through military and economic strength, but through a web of legal and institutional mechanisms that allow it to regulate international trade, finance, and investment. These toolkits confer what is sometimes called “legal power” or “jurisdictional leverage,” and they underpin U.S. hegemony more durably than raw force alone.

In the early post–World War II era, the United States championed multilateral cooperation. Under President Franklin Roosevelt and his successors, the foundations of the modern global architecture — the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and trade institutions — were built to manage international relations, economic development, and trade rules. Over time, however, many countries have come to view these institutions as serving American interests under the guise of universality; meanwhile, the U.S. itself has sometimes flouted the rules it once championed.

Historically, the U.S. has oscillated between isolationist impulses and active global leadership. After World War I, the U.S. retreated into isolationism; but by World War II and afterwards it embraced global engagement and institution-building. In the post-colonial era, the U.S. actively promoted globalization, liberalization, and open markets — benefiting in large part from privileged access, capital, and intellectual property frameworks. Having reaped the gains from this order, the U.S. now sometimes pivots toward protectionism, asserting national interests in tariffs, immigration controls, and supply-chain restrictions. Indeed, this pendulum swing is not new: the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, the Nixon administration’s 1971 termination of dollar–gold convertibility, the Washington Consensus of the 1990s, and the “Make America Great Again” agenda all reflect this tension.

What underlies this apparent “flip-flop” is not a principled ideology but a pragmatic calculation of dominance. The consistent element is not always free trade or autarky, but legal and institutional leverage. Two broad categories of power stand out: trading powers and financial powers. The U.S. uses these to impose costs and shape behavior globally, often unilaterally and irrespective of broader consensus.

Financial Powers: OFAC and SWIFT

The Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) is a central arm of U.S. financial influence. As a bureau of the U.S. Treasury Department, it administers and enforces economic and trade sanctions. It maintains the Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) list, which names individuals, companies, banks, and vessels with which U.S. persons and institutions are prohibited from transacting. OFAC’s powers include freezing assets within U.S. jurisdiction and blocking U.S. dollar transactions. Because most cross-border payments funnel through U.S. banks or American correspondent banking relationships, OFAC effectively exercises extraterritorial reach. Even non-U.S. banks risk secondary sanctions for dealing with SDNs, thereby propagating U.S. influence across global finance.

The Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), headquartered in Belgium, is the messaging backbone for international interbank transfers. While SWIFT is not a bank itself, its infrastructure is essential to settle cross-border payments. Though in principle neutral, SWIFT comes under intense U.S. and EU pressure in practice. Notably, Iran’s banks were expelled from SWIFT in 2012, and Russia faced disconnects in 2022. Without access to SWIFT, sanctioned countries struggle to execute trade and financial flows, even if alternative channels exist. Because most banks globally rely on dollar-based clearing corridors, the U.S. has substantial indirect influence over SWIFT’s enforcement decisions.

Together, OFAC and SWIFT form the financial foundation of U.S. sanctions. They allow Washington to choke off capital, restrict liquidity, freeze foreign holdings, and disrupt global commerce — all without firing a shot.

Trading Powers: Section 301, IEEPA, and More

Parallel to financial leverage, the United States uses statutory tools to impose trade restrictions and sanctions. A central tool is Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. Under Section 301, the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) may investigate foreign trade practices deemed “unjustifiable, unreasonable, or discriminatory,” and, if unresolved through negotiation, impose countermeasures including tariffs — unilaterally and without the need for WTO approval.

The operation of Section 301 is sequential: the USTR initiates an investigation (either proactively or in response to domestic industry complaints), identifies trade barriers, recommends actions, and, failing resolution, implements retaliatory measures. Historically, the U.S. used Section 301 aggressively against Japan in the 1980s and 1990s over auto and semiconductor access. More recently, it has been wielded against China over intellectual property practices, market access, and trade imbalances.

Beyond Section 301, U.S. law grants powerful authorities to its executive branch through statutes such as:

- International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA, 1977): Allows the President, once a national emergency is declared, to regulate commerce and impose sanctions.

- Trading with the Enemy Act (1917): Historically used during wartime, still a foundation for certain sanction regimes.

- Magnitsky Act (2012, expanded globally 2016): Enables sanctions against individuals and entities for human rights abuses or corruption.

- Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA, 2017): Imposes consequences on Iran, Russia, and North Korea, and penalizes third countries that engage with them.

In combination, these statutes constitute a robust arsenal with which the U.S. can project coercive pressure beyond the bounds of simple diplomacy.

Legality and International Norms

From the vantage of U.S. domestic law, sanctions pose no problem: Congress and the President possess broad legal authority to restrict commerce, freeze assets, and penalize foreign actors. But under international law, the picture is more contested.

The United Nations Charter vests authority to sanction member states in the Security Council (Articles 39–41). Actions taken by the U.N. in response to threats to peace are binding under international law. In contrast, unilateral sanctions — those imposed by one state outside a Security Council mandate — lack explicit sanction in the Charter. Critics argue that such measures breach principles of sovereignty, non-intervention (Article 2(7)), and sovereign equality (Article 2(1)). They may also conflict with human rights norms when they disproportionately harm civilian populations.

It should be noted that US has imposed heavy import duties on Indian imports to the extent of 50% effective 27 August including 25% punitive duty for import of Russian oil. Then again it has announced imposing 100% import duties on branded pharmaceuticals effective October 1st. If we add together all the draconian steps by US Administration in Trump2.0 era, being the exorbitant tariffs, H-IB Visa restrictions, indirect sanctions on Chabahar port activities it appears that India is being harshly put under pressure to sign the bilateral trade agreement at the gun point towards US trade advantage unilaterally for which We should be alert and determined in our own national interests.

Trade restraint adds another layer of complexity. Many U.S. trade-based sanctions potentially conflict with WTO obligations. The U.S. commonly relies on Article XXI (“national security exception”) of the GATT to justify measures it deems necessary for its security. WTO panels have sometimes examined these claims, but enforcement is weak in practice, especially against a major power like the U.S.

In pragmatic terms, the unilateral legal authority of the U.S. overrides many objections. Because of the dollar’s dominance and the dependence of global finance and trade on American systems, few countries risk defiance. Whether or not the sanctions are legally “legitimate,” their practical effect is near-absolute compliance in many cases.

Illustrative Case Studies

Cuba: The U.S. embargo on Cuba, initiated in the 1960s, is among the longest-running unilateral sanctions regimes in history. Each year, the U.N. General Assembly votes overwhelmingly to condemn it: in 2024 the tally was 187 in favor of ending it, two against (U.S. and Israel), and one abstention. The embargo has inflicted severe economic hardship on Cuba, restricting trade, investment, and travel. Yet it has achieved little in terms of political transformation, making it more a symbol than a success story.

Iran: Between 2006 and 2015, the U.N. Security Council imposed sanctions on Iran’s nuclear and missile programs under binding U.N. authority. After the 2015 nuclear deal (JCPOA), many of those were lifted. But in 2018 the U.S. withdrew from the deal and re-imposed sweeping unilateral sanctions targeting Iran’s oil exports, banking sector, shipping, and foreign enterprises. These extraterritorial sanctions go beyond U.N. mandates and have been criticized as violations of international law. Their economic effects were dramatic: oil exports collapsed, currency devalued sharply, inflation soared, investment dried up, and ordinary Iranians bore the brunt.

Russia: Russia presents a special challenge to whole-of-world sanction regimes: as a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council, it can veto efforts to sanction itself. Therefore recent sanctions — first after Crimea in 2014 and more intensively after the 2022 invasion of Ukraine — have been unilateral or coordinated among Western allies rather than U.N. mandates. These measures target Russian banks, oligarchs, technology imports, energy exports, and central bank reserves. The effects have been serious — restricted access to Western finance, capital flight, technology gaps — but Russia has mitigated through pivoting toward China, India, and alternative trade networks. The legality of these sanctions remains contested, but their geopolitical and financial impact is undeniable.

Venezuela: Venezuela’s crisis is multi-causal (mismanagement, collapse of oil prices, political dysfunction), but sanctions have amplified the pain. U.S. measures have restricted access to foreign currency, cut off oil sector financing, and limited investment. Analysts estimate billions in lost oil export revenue annually attributable to sanctions. The suffering is profound across a struggling population.

North Korea: North Korea has faced both binding U.N. sanctions and additional U.S. unilateral measures. Sanctions have squeezed its foreign trade — particularly exports and imports — and isolated it from much of global finance. Though its regime survives, sanctions have limited its economic options, making it heavily dependent on a few partners like China.

Recent Addition: H-1B Visa Restrictions & Immigration Levers

In the broader toolkit of U.S. leverage, immigration and visa policy are increasingly used as instruments of control and bargaining. The H-1B visa program — which allows U.S. companies to hire foreign workers in specialty occupations — has recently come under stricter scrutiny and tighter rules. These restrictions function as both domestic (protecting U.S. labor) and foreign policy (discouraging outsourcing or tech dependency).

Recent changes have included higher scrutiny of applications, increased demands on employers, more denials or requests for additional evidence (RFEs), and policy proposals to cap or reduce available slots. While not sanctions in the classical sense, these immigration controls can discourage foreign talent mobility, tighten tech transfer flows, and impose additional compliance burdens on foreign firms.

By restricting the mobility of human capital, the U.S. adds another layer to its dominance toolkit. Companies in other countries that depend on access to U.S. talent or R&D exchange may find themselves constrained. These visa levers complement trade and financial tools, reinforcing U.S. exceptionalism not just in capital flows, but in knowledge flows as well.

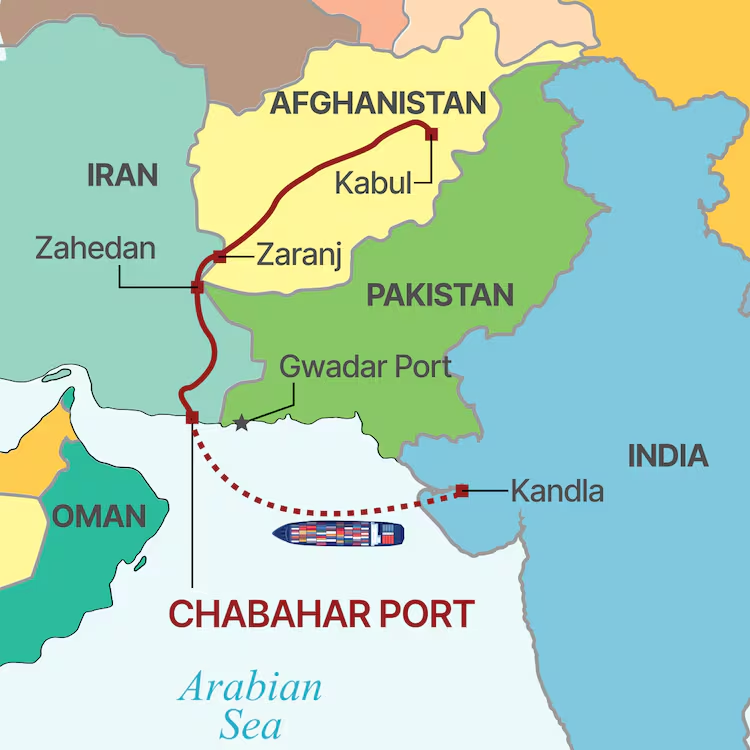

India’s Stakes: Chabahar Port and Strategic Exposure

Though India has not been a principal target of U.S. sanctions in most recent decades, it has experienced spillover effects from U.S. policies — especially when sanctions on third countries impact Indian investments and trade corridors. One prominent example is the Chabahar Port in Iran, intended as India’s gateway to Afghanistan and Central Asia bypassing Pakistan.

The U.S. at times granted India waivers to pursue its Chabahar commitments, but the revocation of such exemptions or tightened sanction enforcement directly threaten India’s investment in port infrastructure, rail links, and transit corridors. Indian firms and the government may struggle with financing, insurance, transaction clearance, and contractual risk if U.S. secondary sanctions or financial restrictions bite. Thus, even when India is not the direct target, U.S. legal toolkits can intrude on its strategic autonomy.

Concluding Reflections

In the 21st century, American hegemony is as much about jurisdictional control as it is about military bases or economic scale. The U.S. has built and continues to expand a legal-technical architecture — OFAC, SWIFT influence, Section 301, IEEPA, the Magnitsky Act, visa rules and more — that lets it regulate global trade and finance almost at will.

These tools empower the U.S. to shift between globalist and protectionist postures as circumstances demand, maintaining dominance even when rhetorical commitments to multilateralism fade. They impose significant costs on target states, often with minimal recourse under international law. And they extend influence over countries that may not be directly targeted but whose strategic projects intersect with the domains of American financial or legal reach.

While critics decry the humanitarian, legal, and sovereignty implications, the practical reality is that many nations and corporations must comply regardless. The ongoing debate — over de-dollarisation, alternative payment systems, digital currencies, regional trade blocs, and visa sovereignty — reflects the struggle to reduce dependence on U.S. legal and financial supremacy. As the global order evolves, resisting or reshaping this dominance may become one of the great strategic challenges of our time.

Amidst the global turmoil and the economic uncertainties, Swadeshi is the only panacea for global peace and prosperity. It is high time that the global community comes together under the leadership of India to collectively create an alternative global system and establish an innovative legal framework whereby to fight against the unilateral coercive legal structure of USA for long term peace and harmony around the World.

The Author is National Co-convenor, Swadeshi Jagran Manch.