India, positioned at the intersection of major geopolitical and economic currents, has the opportunity to emerge as a stabilising middle power—provided it invests in resilience, technological capability, strategic autonomy, and a balanced foreign policy. — Dr. Dhanpat Ram Agarwal

Introduction

The global geopolitical environment has entered a phase of unprecedented turbulence. The post 1945 order—anchored in U.S. strategic leadership, multilateral institutions, and economic globalization is weakening. For nearly eight decades, the world operated under a relatively stable architecture shaped by institutions such as the United Nations, the IMF, the World Bank, and later the WTO. The most significant driver of contemporary instability is the intensifying competition between the United States, China, and Russia. From 1991 to 2010, globalization was driven by free trade agreements, supply chain optimization, and financial liberalization. This era has decisively ended. The financial system has become a tool of geopolitical coercion. The freezing of sovereign reserves and SWIFT restrictions have accelerated search for alternatives to US Dollar as a reserve currency. The process of De-dollarization has begun, which means reducing dependence on the U.S. dollar. Mechanisms of de-dollarisation include local currency settlements, gold accumulation, and alternative payment networks.

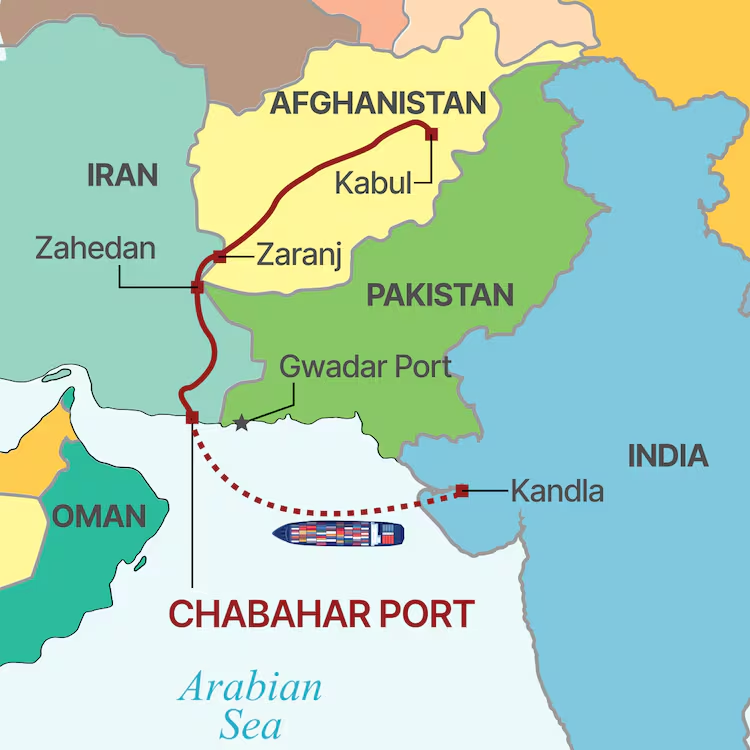

Geopolitics and geo-economics have started changing the global landscape and the tools and the nuances of globalisation. The world currently faces major conflict theatres including Ukraine, Gaza, Red Sea, Sahel region of Africa, Sudan, Taiwan Strait, and the India–China border. Technology is the new foundation of national power. Semiconductors, AI, quantum computing, and cyberwarfare shape national capabilities. Demand for rare earth minerals, such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, rare earths, and uranium has exploded due to the energy transition and digital technologies. BRICS expansion reflects the shift toward multipolarity and demands for institutional reform and financial diversification. India stands at the intersection of Western partnerships and Global South leadership, leveraging multi-alignment for national interest. India must navigate currency volatility, commodity disruptions, and technology access challenges through resilience-building measures. India faces a two-front security challenge along with maritime threats and cyber vulnerabilities. India must strengthen sovereignty across finance, technology, defence, and energy while leading Global South platforms.

The world today is undergoing one of the most turbulent periods since the end of the Second World War. The post-1945 international order—built on U.S. hegemony, multilateral institutions, the dollar-centric financial system, and expanding globalisation—is facing deep structural stress. Geopolitical rivalry has resurfaced, trade and technology are increasingly weaponised, supply chains are fragmenting into blocs, financial flows are becoming politicised, and technological dominance has emerged as the cornerstone of national power. These overlapping disruptions constitute a long-term transition toward an uncertain multipolarity, producing what may be called a phase of “global turmoil.”

The Structural Breakdown of the Old Order

For nearly eight decades after WWII, the world operated under a U.S.-led security and economic architecture. The UN, IMF, World Bank, and later the WTO shaped global rules, while the United States acted as a guarantor of security and global trade remained deeply integrated. This model has steadily weakened since the 2000s, accelerated by the 2008 financial crisis, the rise of China, the resurgence of Russia, domestic polarisation in the West, and post-COVID systemic shocks.

American hegemonic capability has been eroded by strategic overstretch, fiscal pressures, and internal political conflict. Meanwhile, global institutions created in the mid-20th century have failed to reform, leading to legitimacy deficits and the rise of parallel platforms such as the BRICS, SCO, and AIIB. The economic centre of gravity has decisively shifted to Asia, driven by China’s rise and India’s growing economic weight. Technological revolutions in AI, quantum computing, cyber capabilities, and digital finance have disrupted traditional power balances and introduced entirely new domains of contestation. The revival of territorial conflict—from Ukraine and Gaza to the Indo-Pacific—further indicates that assumptions of post-Cold War stability have collapsed.

Great-Power Rivalry as the Core Engine of Turbulence

At the heart of global turmoil lies intensifying great-power rivalry. The U.S.–China relationship is now the defining contest of the century, spanning trade, technology, naval power, cyber operations, rare earths, semiconductors, and competing development models. Unlike earlier disputes, this competition is structural and long-term, rooted in incompatible strategic visions.

Separately, U.S.–Russia confrontation over Ukraine has revived bloc politics reminiscent of the Cold War, triggering NATO expansion, sweeping sanctions, and sharp geopolitical realignments in Europe and energy markets. China and Russia, despite differing interests, have deepened their strategic partnership across Eurasia, UN platforms, energy markets, and financial networks, thereby accelerating the emergence of a non-Western sphere of influence.

Economic Fragmentation and the End of Hyper-Globalisation

The era of hyper-globalisation (1990–2010) was marked by free trade, just-in-time supply chains, and financial liberalisation. This phase has ended. The world now moves toward “managed globalisation” or economic blocs defined by trust, security, and strategic alignment. Supply chains are being reorganised through friend-shoring, near-shoring, and “China+1” strategies. Countries prioritise resilience and national security over efficiency. Trade disputes and technology restrictions—especially in chips, AI accelerators, and telecom equipment—have become instruments of statecraft.

Regional trade blocs such as RCEP, USMCA, the India–Middle East–Europe corridor, IPEF, and renewed EU industrial policies reflect the emergence of fragmented economic ecosystems. Energy markets are similarly realigning due to sanctions, new shipping chokepoint risks, and the shift toward LNG and renewable technologies.

Weaponisation of Finance and the Push Toward De-Dollarisation

Financial systems have become an active geopolitical battlefield. Over 20,000 Western sanctions are in force—targeting Russia, Iran, Venezuela, North Korea, and major Chinese firms—turning compliance into a global enforcement tool. The freezing of Russia’s $300 billion in reserves in 2022 marked a historic moment, signalling that even sovereign assets are not secure from geopolitical decisions. Restrictions from SWIFT and pressure on global banks have further exposed the vulnerability of countries dependent on dollar-denominated systems.

This environment has intensified global efforts toward de-dollarisation. While the dollar remains dominant, countries now seek insulation from U.S. financial leverage. Local-currency settlements, China’s CIPS, BRICS financial cooperation, gold accumulation, and experiments with CBDCs indicate a gradual shift toward a more diversified monetary landscape.

De-Dollarisation: Meaning, Origins, and Limits

Dollarisation refers to the near-universal use of the U.S. dollar in global trade, commodity pricing, banking, and reserve holdings. Its dominance began with the Bretton Woods system (1944), which established fixed exchange rates anchored to the dollar—convertible into gold at $35 per ounce. This was supported by U.S. economic strength and gold reserves, which accounted for 70% of global holdings after WWII.

However, by the early 1970s, U.S. deficits and global imbalances made the gold peg unsustainable. The Nixon Shock of 1971 ended dollar–gold convertibility, effectively shifting the global system to fiat currencies. The U.S. then secured the petrodollar system through a 1974 pact with Saudi Arabia, ensuring that global oil was priced in dollars—a key factor sustaining dollar demand.

Today’s push for de-dollarisation arises from sanctions fear, geopolitical realignment, digital currency innovation, and rising global trade within Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. Countries want monetary sovereignty, protection from financial coercion, and reduced exposure to U.S. fiscal instability.

However, full de-dollarisation faces major constraints: no currency matches the liquidity, rule-of-law environment, or depth of U.S. capital markets; the yuan is not fully convertible; the euro suffers from structural fragility; and commodity markets remain dollar-priced. Therefore, the shift will be incremental and partial, not revolutionary.

Global Conflict Zones and Systemic Instability

The world currently faces multiple, overlapping conflict theatres: the Ukraine war, Israel–Hamas and Middle East escalation, Red Sea shipping disruptions, Taiwan Strait tensions, Sahel region coups, Sudan’s civil war, and India–China border militarisation. These conflicts raise global energy prices, increase insurance and freight costs, destabilise food markets, and accelerate defence spending. They also reshape diplomatic equations and influence global supply chains.

Technology as the New Geopolitical Frontier

Technological dominance—particularly in AI, quantum computing, semiconductors, and cyber warfare—now defines national power. Control of chip supply chains determines military technology, AI capabilities, digital sovereignty, and economic competitiveness. Quantum breakthroughs promise to revolutionise cryptography, intelligence, and financial security. Cyberspace has become a constant battlefield, where attacks on critical infrastructure, finance, and communication systems pose multidimensional security risks.

Critical Minerals and Commodity Geopolitics

The green transition and digital expansion have elevated the strategic relevance of lithium, cobalt, nickel, rare earths, graphite, and uranium. Control over mines, refining capacity, and processing nodes is now a major determinant of long-term industrial and strategic security. Nations are racing to secure mineral supply chains, diversify sources, and reduce dependence on single-country monopolies, particularly China.

BRICS+ and the Rise of the Global South

The expansion of BRICS into BRICS+ signifies one of the most important shifts in global governance. It includes major commodity producers and fast-growing economies across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. BRICS+ aims to reform global financial structures, promote non-dollar trade, create independent development financing mechanisms, and build strategic autonomy from Western-controlled institutions. More broadly, the Global South is reasserting agency after decades of under-representation in global decision-making.

India’s Strategic Position in a Turbulent World

India stands at a distinct advantage as a stabilising power in an increasingly multipolar landscape. Its multi-alignment strategy enables cooperation with diverse platforms—Quad, BRICS, G20, SCO, ASEAN, BIMSTEC, and I2U2—without entanglement in exclusive blocs. India benefits from its demographic dividend, expanding digital infrastructure (UPI, Aadhaar, ONDC), favourable geography, growing defence industry, and its role as a bridge between the Global South and Western partners.

However, challenges remain: border tensions with China, energy import dependence, constraints in advanced technology access, and exposure to global financial volatility. India must strengthen its foreign exchange buffers, promote rupee trade settlement, secure critical minerals, and accelerate semiconductor, AI, and cyber capabilities. Defence modernisation—particularly in naval power, missile systems, drones, and integrated intelligence—is essential to managing a two-front security scenario and growing Indo-Pacific tensions.

Economic and Security Implications for India

Global turmoil affects India through currency volatility, commodity price shocks, disrupted supply chains, and tightening global financial conditions. To mitigate these risks, India must deepen economic resilience by strengthening reserves, diversifying energy sources, expanding strategic petroleum storage, building food security buffers, and developing next-generation infrastructure. Accelerated investment in AI, semiconductors, green energy, and quantum technologies will be crucial for long-term economic sovereignty.

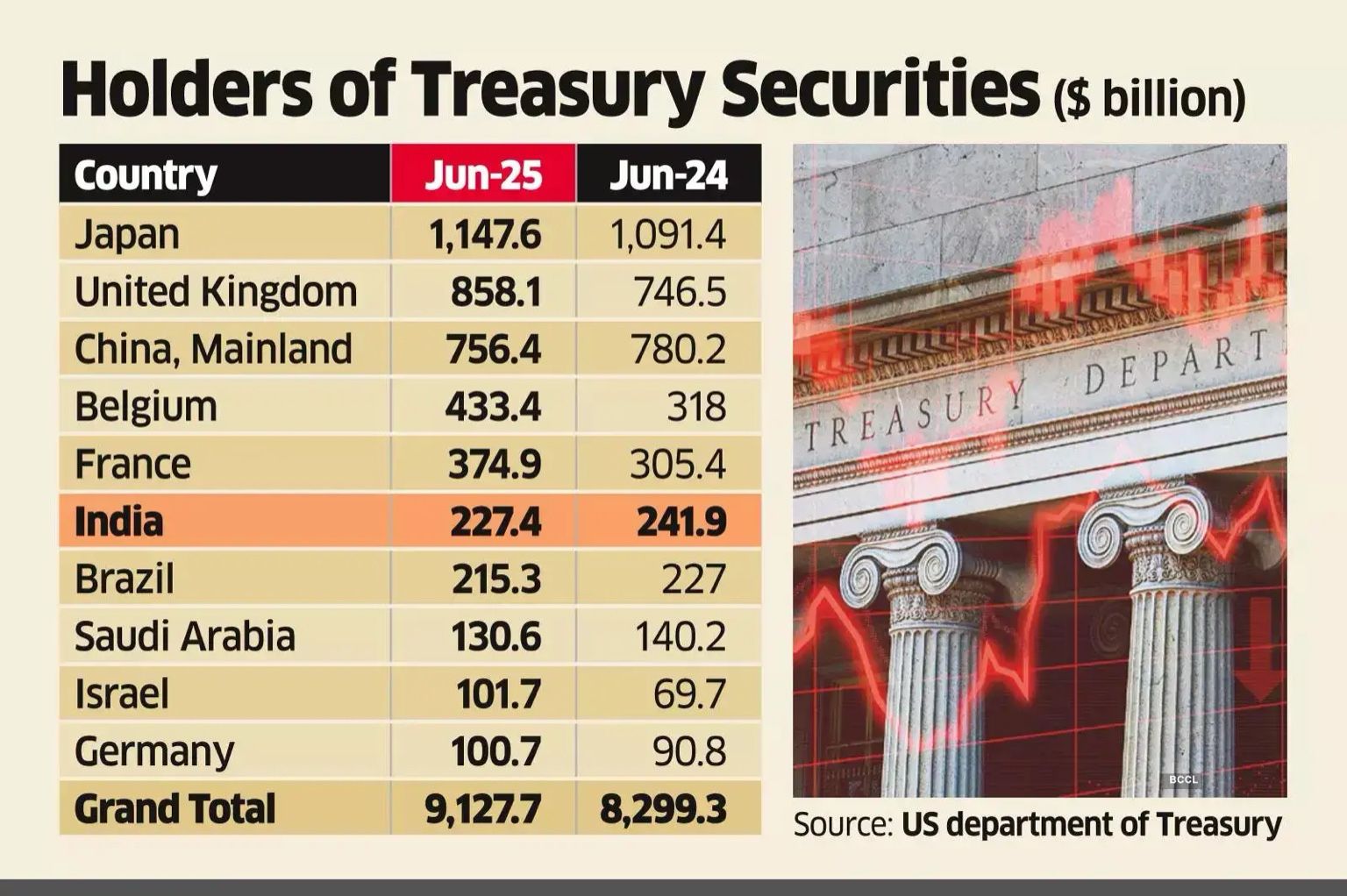

The Dollar’s Future and the Risks of U.S. Debt

The dollar remains the world’s primary reserve currency, but rising U.S. debt—over $37.5 trillion—poses systemic risks. High debt-to-GDP ratios, fiscal deficits, political gridlock, inflation cycles, and interest-rate volatility undermine confidence in long-term dollar stability. Over-concentration of global reserves in USD exposes the world to U.S. domestic vulnerabilities. Sanctions-driven weaponisation of the dollar payment system further motivates nations to diversify reserves and build independent financial channels.

Nevertheless, a total shift away from the dollar is improbable in the near future due to the absence of strong alternatives. The world is moving toward diversification—not replacement—through regional settlement mechanisms, multi-currency reserves, and digital financial architectures.

Conclusion

Global turmoil today reflects a structural transition toward a competitive multipolar order. The forces reshaping the world—geopolitical rivalry, financial weaponisation, technological disruption, energy realignment, and the search for currency sovereignty—are long-term and irreversible. De-dollarisation will advance gradually, driven by geopolitical distrust, technological innovation, and the rise of non-Western economic centres. Yet the dollar will remain dominant until alternative currencies acquire comparable depth, trust, and global acceptance.

India, positioned at the intersection of major geopolitical and economic currents, has the opportunity to emerge as a stabilising middle power—provided it invests in resilience, technological capability, strategic autonomy, and a balanced foreign policy. The coming decade will demand agility, innovation, and sustained diplomatic leadership as the world navigates its most consequential transformation since 1945.

Dr. (CA) Dhanpat Ram Agarwal, National Co-convenor, Swadeshi Jagran Manch